Scientists have known for a while that boys are four times as likely to receive an autism diagnosis as girls, and they are also more likely to receive this diagnosis at a younger age—often before turning five. Co-occurring psychiatric and other medical conditions could be contributing to these sex differences, but until recently, obtaining reliable data about the timing of a child’s autism diagnosis and co-occurring health conditions has been challenging.

That problem might be finding a solution.

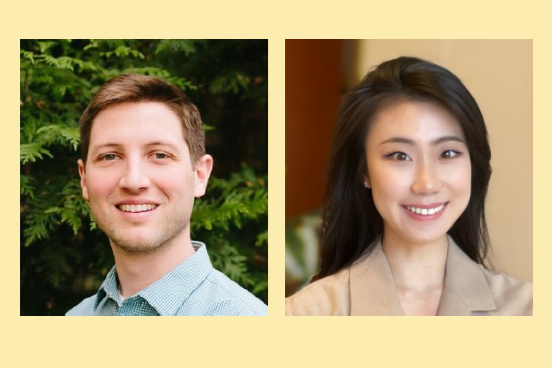

Enter biostatisticians Matthew Engelhard, M.D., Ph.D., and Zhengyi (Gloria) Gu, whose recent study of sex differences in the age of autism diagnosis and their links with co-occurring conditions was published in December 2023 in the journal Autism Research.

Engelhard, assistant professor of biostatistics and bioinformatics at Duke University, worked with his student Gu to probe the question of why girls are diagnosed later than boys. They used de-identified electronic health records (EHR) data from Duke Health to conduct a retrospective analysis of patients who received an autism-related diagnosis between 2014 and mid-2021.

What they discovered both clarifies the sex-differences findings and raises new questions.

Gu and Engelhard found that girls with autism are more likely to be diagnosed with depression or anxiety in the two years before they receive a diagnosis of autism. When they accounted for these diagnoses within their computational model, they observed that the age difference between girls and boys at autism diagnosis went away.

“The anxiety and depression diagnoses seem to be explaining the difference between girls and boys in terms of when they are diagnosed,” Engelhard says. “But we can’t yet say why. We can only say that these psychiatric conditions appear to be part of a pathway toward a delayed autism diagnosis for girls.”

Across the board, girls are more likely to receive diagnoses of depression or anxiety than boys. For girls who receive this diagnosis and are later found to be autistic, does that mean the original diagnostic assessment was incorrect?

“We don’t know the answer to that question yet,” says Engelhard.

EHR data also showed that the timing of an autism diagnosis is more complicated than earlier studies suggested. Girls were more likely to be diagnosed either very early (before age three) or very late (after age 11), whereas boys were more likely to be diagnosed between ages three and 11. And while visits for anxiety and mood disorders were more common in girls and associated with a later autism diagnosis, visits to otolaryngology were more common in boys—and associated with an earlier autism diagnosis.

“The boys’ co-occurring medical diagnoses are linked to earlier autism evaluation,” Engelhard says. “The girls’ co-occurring diagnoses are not.”

Diagnostic overshadowing is one possible reason why girls and boys tend to be diagnosed at different ages, with autism in girls potentially overshadowed by conditions such as anxiety. But diagnostic delays could also be attributed to bias, with providers less attuned to the ways autistic features show up in girls and more likely to attribute a girl’s struggle with, say, social communication to a psychiatric rather than a neurodevelopmental condition.

Still, explaining why these sex differences exist might be less important than simply getting the word out that they do exist, says Engelhard.

“If we can make providers aware that anxiety and depression diagnoses are common in autistic girls, and that they’re associated with delays in autism diagnosis, then that awareness alone can help change care,” he says. “And that’s important because many autistic girls are not getting support soon enough, and others never receive an autism diagnosis.”

The study forms part of Engelhard’s NIH K01 Mentored Research Scientist Career Development Award, a five-year grant in which he aims to apply EHR data to develop tools for predicting neurodevelopmental conditions and begin implementing those tools at Duke Health.

Gu, who earned her master’s in biostatistics in May 2023, says she found working on this grant an ideal mentoring experience. She is the lead author on the sex differences paper, and she recently accepted a position as a biostatistician at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she works for Priya Palta in the cardiovascular research space.

“I really enjoyed my involvement in Dr. Engelhard’s project,” Gu says. “I greatly improved my techniques for dealing with raw EHR data, and it made me want to do more to apply these methods to improve healthcare.”

And while Engelhard began his own career by earning an M.D., he says the plan was always to wind up doing what he’s doing today. “I always wanted to build mathematical models for healthcare,” he says. “But I also wanted to make sure providers would actually use them. To do that, I needed to understand what it’s like to be a provider.” He approaches big data with the analytical eye of a computational scientist and the keen observational skills of a physician. “It's the right time to be doing work in this area,” he says. “These questions are where I want to focus my energy. We need to make these models better and put them to work helping patients and families.”

Gu Z, Dawson G, Engelhard M. Sex differences in the age of childhood autism diagnosis and the impact of co-occurring conditions. Autism Res. 2023 Dec;16(12):2391-2402.